I recently received the following question from a former reloading student:

I've been reloading .45 ACP with 200gr lead semi-wadcutter bullets. I've worked up a very accurate load, but 4 or 5 rounds out of 100 will not chamber in my pistol. At another shooter's suggestion, I bought a Dillon Case Gage to check my reloads, and found (not surprisingly) that the rounds that won't chamber also won't fit in the gage. All of the rounds were made using the same bulk bullets, from the same manufacturer, with the same setup. I used mixed brass, but it was all from factory ammo that I originally fired in my pistol.

One of the guys at my club recommended that I buy a Lee Factory crimp die, but I'm not sure that my problem is related to the crimp. What am I doing wrong? Will the Factory Crimp Die fix it?

This is a pretty common problem with handgun rounds, and it's not limited to .45 ACP. The root cause is inconsistency, and it can be caused by the components, improperly set dies, and/or sloppy technique.

One of the goals in reloading is to make every round the same. Many reloaders assume that they can accomplish this goal as long as they follow the recipes in the manuals and set up their equipment properly. This is not true 100% of the time - In fact it was only true 95%-96% of the time in the case of the person that asked the question above. The following factors can contribute to the problem described above, especially when several are combined.

Case Wall Thickness and Bullet Diameter Variation

I measured a sampling of 100 mixed .45 ACP cases from seven different manufacturers and the results were surprising. The wall thickness averaged about 0.010",

but I found cases as thin as 0.008" and as thick as 0.013" (US military cases were the thinnest, and Federal and AMERC were the thickest). While the sizing die

will temporarily shrink and uniform the outside diameter of the cases regardless of wall thickness, the expander die and the bullet itself will re-expand the case from

the inside, causing the loaded rounds' outside diameters to vary. If I loaded these cases using perfectly identical bullets, and measured the outside diameter

of the completed rounds, I would see a difference of 0.010" from the smallest to the largest caused entirely by brass thickness variation. This is huge.

Bullet diameter can also be a factor. Cast lead bullets are generally sized 0.001" larger than jacketed bullets of the same caliber. I say "generally" because I've purchased bulk quantities of cast lead bullets from reputable manufacturers that were as much as 0.003" larger than jacketed bullets. Some inexpensive plated bullets can also exhibit excessive diameter variations. The plating process is a difficult one to control, and bullets that are packaged right after the plating process can be inconsistent. Some plated bullets are 'double-struck', which means that they go through an additional final sizing step after plating. These tend to be more consistent.

If 'oversized' bullets are loaded into cases with normal or thin walls, the rounds will likely chamber without problems, but when oversized bullet is combined with a thick-walled case, these two factors combine to make a round that will not fit into a tight chamber (or a case gage).

Case Length

Believe it or not, the length of the case can ultimately affect a round's ability to chamber. Case length affects the amount that the case is belled (see below)

and also the crimp. When you set up your crimp die, the length of the case (and to a lesser extent the thickness) will affect the amount of crimp applied to the

round. Shorter (and thinner) cases will have less crimp, and longer/thicker cases will have more. In my sample of .45 ACP cases, the case lengths of fired

(unsized) cases ranged from 0.878" to 0.895", with Winchester cases grouped near the short end and Federal near the top. If I were to set up the crimp die using

Winchester cases, the Federal cases would end up with more crimp. Depending on the die height setting and the internal profile of the crimp die, the longer/thicker

cases could end up slightly bulged just below the crimp. The bulge may be only a few thousandths of an inch (not easily noticeable upon inspection), but combined

with other factors can result in a round that won't chamber.

Insufficient Case Belling

Many reloaders intentionally set the expander die to flare the case mouth as little as possible. The thinking is that this practice will work the brass less, and

result in longer case life. While this may or may not be true, insufficient case belling can result in some pretty bad ammo. At the worst, insufficient

belling can result in crushed cases and shaved (cast lead) bullets. Even if the damage is not obvious, insufficiently belled cases require more force to seat the

bullet, and can end up with bulges or bullets that seated off-center - either of which can result in ammo that will not gage/chamber.

Even if you think the die is set to provide sufficient flare, if you do your initial setup using a long-ish case, the die will flare shorter cases less; possibly enough to cause the problem described above.

Bullet Seating Technique

The proper way to seat a flat-based pistol bullet is to lightly place it - centered and straight - on top of a properly flared case. Many reloaders - especially those that

reload on a progressive press - rush this process. If you jam the bullet down into the case, or place it at too much of an angle, it might not seat straight. You can

end up with a completed round that has a pronounced bulge on one side of the case (see Figure 3). This happens more frequently when the case is insufficiently flared to begin with.

The problem is exacerbated by inexpensive dies with internal clearances generous enough to allow the bullet to enter the die crooked. Some dies (such as the seating dies in Hornady pistol sets) minimize this effect by using a sliding alignment sleeve which pre-straightens the bullet before the die bottoms out and begins to seat. (See Figure 4).

Will the Lee Factory Crimp Die fix the problem?

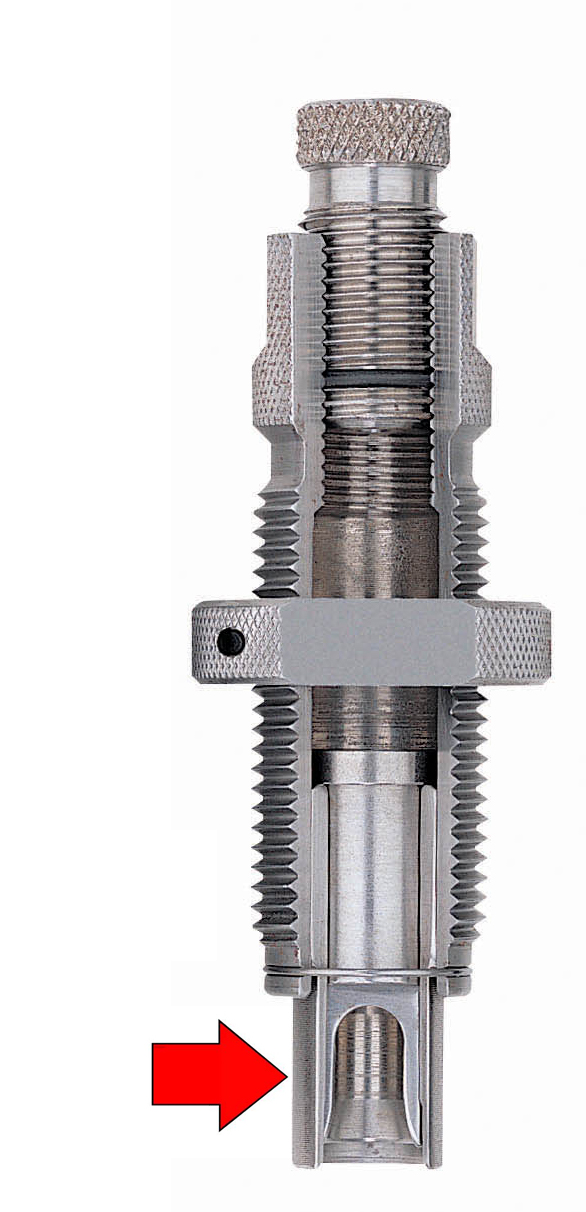

The Lee Factory Crimp die might solve the chambering problem, but in the process it could cause another. The Lee Factory Crimp Die for pistol calibers does more than just

crimp the round. It features an internal carbide sizing ring similar to the one found inside sizing dies, but larger in diameter to accommodate a loaded round.

(NOTE: Never try to run a completed round through a regular sizing die with the decapping pin removed - it's too small).

When the nearly-completed round is forced into the die, the sizing ring squeezes any bulged or oversized rounds down to a dimension that will ensure that they chamber. Sounds good, right? There's a possible drawback though when using the Factory Crimp Die on rounds loaded with lead bullets. If a round loaded with a cast lead bullet is oversized because the case is thicker than normal, and the Factory Crimp Die squeezes it down to a smaller diameter, it will do so by reducing the diameter of the bullet inside the case. Lead is much softer than brass, so the case thickness will remain the same while the bullet diameter is decreased. If the diameter of the driving bands on the bullet (see Figure 5) are made smaller than the bore diameter, hot gases from powder combustion will escape along the sides of the bullet, causing gas-cutting of the bullet which will result in severe barrel leading.

What can I do to prevent this problem?

Pre-Sort Your Brass - Measure the length and thickness of your cases, note which headstamps trend to the long and thick end of the spectrum, sort them out, and reserve them for use with jacketed bullets.

Use Good Bullets -Good bullets are consistent bullets. If your bargain bullets vary in diameter, they might not be such a bargain after all.

Properly Flare the Cases - Reducing the flare does little to extend brass life. Measure a sampling of cases to determine the range of case lengths, and use one of the shorter ones to set up your expander die.

Pay Extra Attention to The Seating Step - Either get a Hornady (or similar) seating die, or take a little extra time to ensure that the bullet is properly placed on top of the flared case.

Also, if you're not using one already, it's a good idea to get a case gage (such as a Dillon, Wilson, or Lyman) to check your finished rounds. A case gage (see Figure 6) is a metal tube that is precisely machined to the dimensions of a very tight chamber. Simply drop the finished round into the gage. If it fits in the gage, it will likely chamber in your gun. Use the gage for spot checks during your reloading session and to check your finished rounds when you are done.